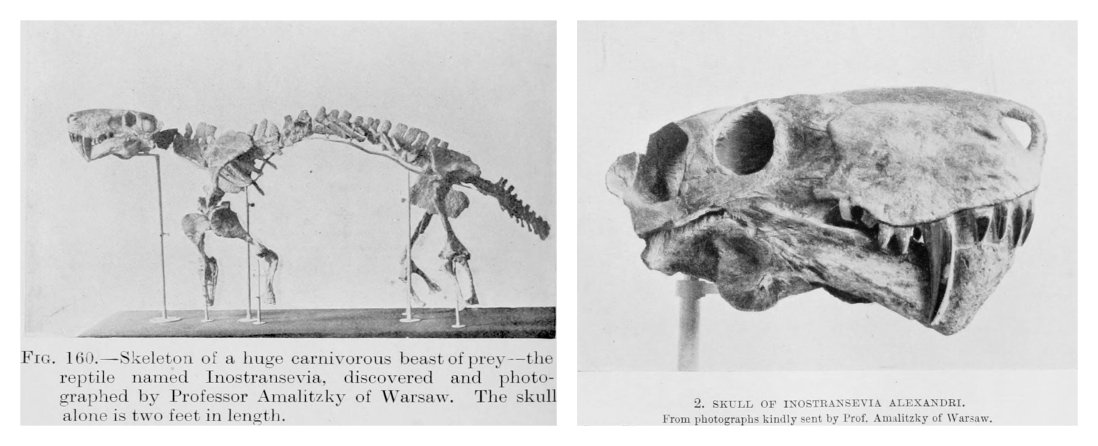

Photographs of Inostrancevia alexandri annae [see addendum] and captions, from Lankester (1905) (left) and Hutchinson (1910) (right).

The authorship of the gorgonopsian genus Inostrancevia, and its type species [see addendum] I. alexandri, has usually been attributed to Amalitzky (1922) (e.g., Tatarinov, 1974; Ivakhnenko, 2001; Kammerer et al., 2023).1 However, they were actually named several years earlier by two different authors. The earliest use of Inostrancevia was by Lankester (1905), who wrote it in captions to Amalitzky’s photographs of the skeletal mount and skull. He probably did not intend to propose it as a new name, and may have been under the mistaken impression that Amalitzky already formally described it. Yet, the clear association between the name and the specimen in the photos counts as an ‘indication’2 according to Article 12.2.7 of the Code (ICZN, 1999). Although a species was not included, that was not required for genera until after 1930 (Article 13.3). Therefore, the genus Inostrancevia was first made available by Lankester. [see addendum]

The earliest use of I. alexandri was by Hutchinson (1910), who also wrote it in captions to Amalitzky’s photos of the skeletal mount and skull. The proposal of a new name here was likely unintentional for the same reason as Lankester. The association between the name and the photographed specimen again serves as an indication under Article 12.2.7. Thus, the species I. alexandri was first made available by Hutchinson. Since it was the first species to be placed in a genus that originally did not contain any, and was the only one at that time, it is the type species by subsequent monotypy (Article 69.3). [see addendum]

Because Lankester explicitly credited Amalitzky with providing both the name and photos, which met the requirements of availability (besides publication), the authorship of Inostrancevia should be cited as Amalitzky in Lankester, 1905 (Article 50.1.1 and Recommendation 51E). [see addendum] Hutchinson only credited Amalitzky with providing photos and not the name, so the authorship of I. alexandri should be cited as Hutchinson, 1910.

Notes

1It was spelled Inostranzevia by Amalitzky, but was changed to Inostrancevia by Pravoslavlev (1927). The latter spelling has since become the most widely-used. Both Lankester and Hutchinson used another spelling, Inostransevia.

2This is a condition which confers availability to a name in the absence of a description. Indications only apply to names before 1931.

Addendum (1/9/2024)

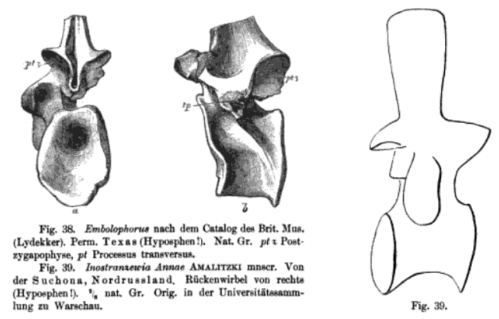

Illustration of a vertebra from Inostrancevia annae and caption, from Huene (1902).

Christian Kammerer has pointed out that there is an even earlier usage of Inostrancevia (see comment below). Huene (1902) published the name Inostranzewia (sic) annae, which he attributed to Amalitzky, in the caption to a drawing of a vertebra. This is an indication and it makes both the genus and species available. The type species of Inostrancevia is I. annae, not I. alexandri (which is a junior synonym), by original monotypy (Article 68.3). As Amalitzky was not credited for the drawing, the authorships of Inostrancevia and I. annae should be cited as Huene, 1902.

References

- Amalitzky, V.P. (1922). Diagnoses of the new forms of vertebrates and plants from the Upper Permian on North Dvina. Izvestiya Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk, VI Seriya, 16, 329-340.

- Huene, F., von. (1902). Übersicht über die Reptilien der Trias. Gustav Fischer.

- Hutchinson, H.N. (1910). Extinct monsters and creatures of other days: A popular account of some of the larger forms of ancient animal life. New and enlarged edition. Chapman & Hall. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.40362

- ICZN. (1999). International code of zoological nomenclature (4th ed.). The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature; The Natural History Museum, London.

- Ivakhnenko, M.F. (2001). Tetrapody Vostochno-Yevropeyskogo plakkata – pozdnepaleozoyskogo territorial’no-prirodnogo kompleksa [Tetrapods of the East European placket – Late Paleozoic territorial natural complex]. Trudy Paleontologicheskogo Instituta Akademii Nauk SSSR, 283, 1-200.

- Kammerer, C.F., Viglietti, P.A., Butler, E., & Botha, J. (2023). Rapid turnover of top predators in African terrestrial faunas around the Permian-Triassic mass extinction. Current Biology, 33(11), 2283-2290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.007

- Lankester, E.R. (1905). Extinct animals. Archibald Constable & Co. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.13370

- Pravoslavlev, P.A. (1927). Gorgonopsidae iz severodvinskikh raskopok V.P. Amalitskogo [Gorgonopsidae from the North Dvina excavations of V.P. Amalitzky]. Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk USSR.

- Tatarinov, L.P. (1974). Teriodonty SSSR [Theriodonts of the USSR]. Trudy Paleontologicheskogo Instituta Akademii Nauk SSSR, 143, 1-250.

Lankestser’s publication does make it an available name, but the authority is listed as Amalitzky in Lankestser’s book. Arguably the citation should then be Amalitzky in Lankestser, 1905.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are correct, I have added an explanation of how the authorships should be cited.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is what is known as “opening a can of worms”. Your attribution of the earliest use of a published name for the giant North Dvina gorgonopsian to Lankester (1905) is incorrect. Friedrich von Huene (1902), in the published version of his Habilitation, “Übersicht Über die Reptilien der Trias”, figures (as Fig. 39, page 36) a vertebra of this animal, labeling it as “Inostranzewia [sic] Annae AMALITZKI mnscr.” Here, see for yourself: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Übersicht_über_die_Reptilien_der_Trias/vGJAAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

If we follow your logic here in terms of recognizing association of a nomen manuscriptum with an image as rendering availability, then two destabilizing possibilities emerge: the type species of this genus becomes “annae Amalitzky in Huene, 1902”, which potentially takes precedence over “alexandri” (if the isolated vertebra Huene figured can be demonstrated to have originated as part of the near-complete skeleton, PIN 2005/1587, that constitutes the holotype of I. alexandri), or Inostrancevia becomes a nomen dubium (if the vertebra, which is not diagnostic for the genus, is not associable with the holotype skeleton), necessitating replacement with the next-available genus name for this gorgonopsian (Amalitzkia Pravoslavlev, 1927). Determination of which of these is the case would require archival work going through Amalitzky’s unpublished manuscripts (either in St. Petersburg or Moscow) to determine which specimen was the basis for Huene’s figure, but of course neither is ideal for taxonomic stability.

Taxonomy has a bad rap among “serious” scientists as meaningless bookkeeping, a general misapprehension that I have long sought to counteract–I consider it a cornerstone of biology and engagement with the details of taxonomic history to be essential. However, things such as that which you are doing here are exactly what they bemoan–pointlessly complicating matters in a way that adds nothing to the science of paleontology and just makes things harder for those of us actually working on these fossils. Merely responding to this post has wasted time that I was otherwise spending writing a paper on gorgonopsian alpha taxonomy, but as it had engendered some confusion among my colleagues I felt it necessary. If you intend to hold strictly to the letter of the Code in a way that maximally disrupts the stability of zoological nomenclature, the least you can do is provide solutions to the problems you are creating. If you were to petition the ICZN to suppress prior uses of Inostrancevia and recognize the species Inostrancevia alexandri as having been named by Amalitzky (1922) to maintain prevailing usage, I would happily write a letter in support, but I am not going to waste more time doing so myself. Rather, I plan to continue using the name Inostrancevia alexandri Amalitzky, 1922 for the conceivable future and treating all prior uses of this name as nomina nuda.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for bringing Huene’s publication to my attention. I posted an addendum about it and corrected my mistakes. With all due respect, ignoring nomenclatural and taxonomic issues does not fix them or serve stability. I have not “opened a can of worms” or “created problems”. They already existed for a long time and would have eventually been brought up by someone else if not me. They were caused by a lack of rigor in the pre-Code era, not by any modern trend. Inostrancevia Huene, 1902 and I. annae Huene, 1902 are indisputably not nomina nuda and are the oldest available names for this taxon. The fact that they were made available by an illustration and caption is not the result of “my logic”, but instead a provision of the Code. As such, they must be properly dealt with and not simply disregarded. I have not submitted a petition to the Commission because I am not a gorgonopsian worker and I trust that the relevant people can handle it appropriately. By attempting to circumvent the rules of the Code, and calling this pursuit a “waste of time”, you are belittling the very study you claim to support. Pretending that these earlier names do not exist only promotes further instability. I will continue to treat them as available until they are officially suppressed by the Commission, and recommend that others do so as well.

LikeLike

Listen, I know how it is. When I started in paleo research as a student, I wasn’t anywhere near a real fossil and did all my work going through the literature and trying to sort out taxonomic problems. My first published paper was about preoccupied names in Synapsida. I thought, “well, this is clearly something that most working paleontologists consider boring ‘bookkeeping’, but I at least find interesting”, and was happy to believe that I was fixing problems so that others wouldn’t have to, that I was making the lives of others easier by not having them expend time and energy on such things. So I would ask you, do you think you are making anyone’s life easier through your work? Do you believe that when future generations of researchers look back on your contributions to the science of paleontology, it will be with approbation and gratitude for the resolution of problems heavy on their minds, and not “what a pain all that was to deal with, best ignore it and move on”? Speaking for myself, I love researching taxonomic history and take pride in knowledge of and adherence to the Code in navigating areas of taxonomic uncertainty. I respect your dedication to these same ideals. But here’s the thing: the Code is not inviolate law, handed down from on high and beyond question by we mere mortals. The Code exists “to promote stability and universality in the scientific names of animals”. It serves *us*, it exists to make the communication of scientific concepts easier for both scientists and the public. When we begin instead to serve *it*, treating taxonomy as a system of byzantine legalese, we destroy the Code’s own spirit. You say that I am belittling a system I claim to support by ignoring inconvenient provisos therein. To that I say that you are belittling the very foundations of nomenclature by treating names as so tawdry a thing that a stray label should contravene a century of continuous usage.

As regards your statement that, having raised this problem, you “trust the relevant people can handle it appropriately”, disclaiming any involvement because you “are not a gorgonopsian worker”, you surely must realize how ridiculous of a sentiment this is. Firstly, are you not writing about gorgonopsian taxonomy here based on your research? Is that not being a gorgonopsian worker? Secondly, this is equivalent to lighting a building on fire, and then when its inhabitants yell, “Put it out!”, turning to them with a shrug and saying, “I’m not a firefighter, I trust the relevant people can handle it appropriately”, and walking away. You conclude your reply above by stating, in essence, “it doesn’t matter if no one else cared about this in the century before I brought it up, them’s the rules and now you all have to follow them.” But the thing is, we don’t. I am a substantial outlier among paleontologists in actually engaging in these sorts of nomenclatural issues to the extent that I do; I can assure you that most not only can, but will, blithely disregard this sort of issue without a care in the world. I have observed that adherence to the Code is nearing an all-time low among zoologists, some of which is simple ignorance, but where it is instead an active choice, it is things such as this that have led to disillusionment among my colleagues. To expand on the earlier analogy, perhaps the situation would be better framed thusly: you walk into a building, yelling, “The building’s on fire! You have to do something!”, but the inhabitants look around, see that nothing is amiss, and disregard your shouts before returning to their business, somewhat annoyed by the unnecessary row. I would ask that you ponder upon and unpack why this is a source of consternation to you. Is it so deep-seated within you, the anger that *A Law* has been broken and this cannot be permitted? Why do we have laws, anyway? If a parent were to steal a loaf of bread to feed their starving child, would you be the one leaping up to turn them in? I cite such a trite example not as a facile reductio, but because, as stated above, I really do respect what I think you are *trying* to do with your taxonomic and nomenclatural research, and want you to devote serious thought to what you want the legacy of that research to be. Is it slavish absolutism to the words laid down by a small group of men a generation ago, effects be damned? Or is it to advance scientific understanding and make easier the work of others devoted to that goal?

Let me conclude with a reminiscence. While I was a PhD student, some senior colleagues were working on a paper concerning the cynodont family Trirachodontidae. Knowing me to be well-versed in matters nomenclatorial, with a copy of the Code always close at hand, they asked me about the type species of the genus Trirachodon. Seeley (1895), the namer of Trirachodon, included two species in the genus: T. kannemeyeri and T. berryi. Seeley (1895) designated kannemeyeri as the type species, and for the next century and more, kannemeyeri was treated as such by synapsid workers. I had to tell them, however, that because in the plates of a paper (Seeley, 1894) which, by inadvertent happenstance of publication history, predated Seeley (1895), there is figured a specimen labeled “Trirachodon berryi”, under Art. 12.2.7 of the Code, the authorship of Trirachodon must go to Seeley (1894) and, by monotypy, the type species of Trirachodon must be T. berryi. I was only following the rules of nomenclature in telling them this. I have regretted this decision ever since, and it has caused nothing but trouble for cynodont workers (as, with many analyses indicating non-monophyly of T. kannemeyeri+T. berryi, the once inviolate generic name of “T.” kannemeyeri has gone into flux). Indeed, it is such that I am now taking measures to rectify my mistake and formally reasserting kannemeyeri as the type species of the genus. Hopefully that resolves things once and for all, but I lament taking the time to do so, feeling more acutely now the debt of years and the preciousness of our time here on Earth. I share this as a warning: I see in you some of my own past, so please don’t make the same mistakes I did.

LikeLike