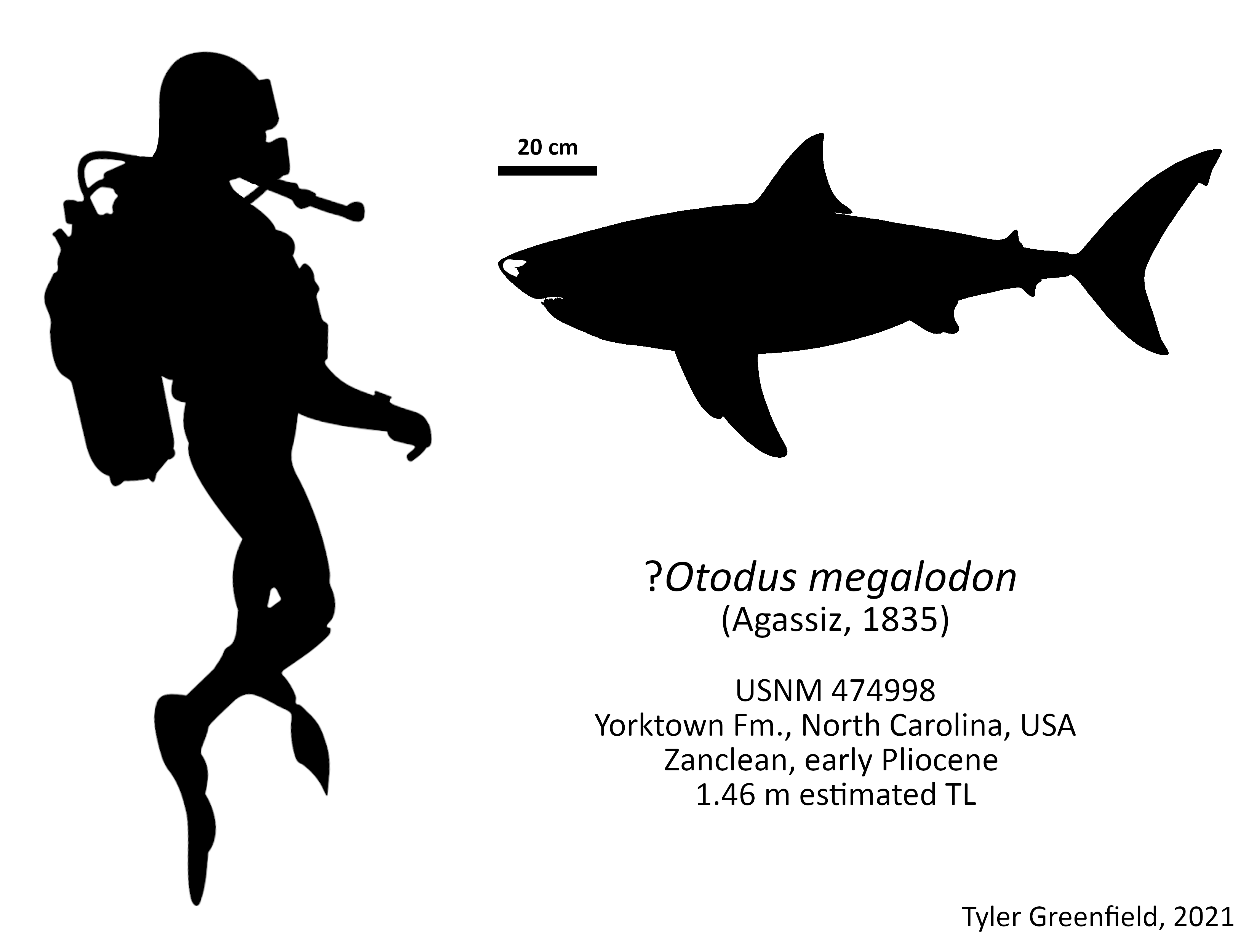

A partial rostral cartilage possibly belonging to a fetal O. megalodon.

A common myth about extinct sharks is that we only find their teeth and nothing else. Of course, this is absurd as there are many sites around the world where shark body fossils (both the skeleton and soft tissues) are found. These are not all new discoveries either, with exceptional specimens having been known since the 1700-1800’s. Examples include Galeorhinus cuvieri from Monte Bolca in Italy (Volta, 1796; Agassiz, 1835) and Scapanorhynchus lewisii from Sahel Alma in Lebanon (Davis, 1887; Woodward, 1889). This fact has still not prevented the myth from spreading to one of the most famous extinct groups of sharks, the megatooths, family Otodontidae.

While no megatooths have soft tissues preserved like Galeorhinus or Scapanorhynchus [see second addendum], there are quite a few skeletal specimens known from this family. These are often overlooked when reconstructing megatooths, especially Otodus megalodon, and the “only teeth” claim appears frequently. In order to put this to rest, I have compiled a list of published megatooth skeletal fossils and references at the bottom of this post. In total there are 14 specimens – 6 partial vertebral columns associated with teeth (1 of these with jaws), 2 partial vertebral columns with no associated teeth, and 6 isolated rostral nodes. 5-6 species are represented – Cretalamna hattini, Otodus obliquus, O. auriculatus, O. angustidens, O. megalodon, and possibly Parotodus benedeni.

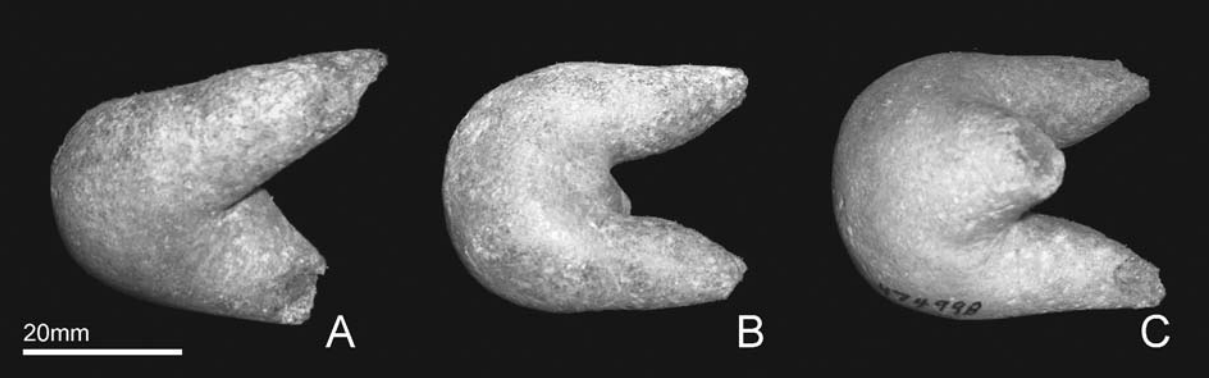

The same rostral node as the reconstruction above, from Mollen & Jagt (2012).

The rostral nodes are particularly obscure and have interesting implications for megatooth life appearance. They were found in Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina and first identified as belonging to porbeagles, Lamna sp. (Purdy et al. 2001). However, Mollen & Jagt (2012) reanalyzed them and ruled out that they were from porbeagles, makos (Isurus), or great whites (Carcharodon) based on their morphology. Instead they likely belonged to one of the two otodontids found at Lee Creek – O. megalodon or Parotodus benedeni. This suggests that at least some megatooths had blunt, robust rostral cartilages superficially similar to Lamna. It also indicates that this feature was present in the common ancestor of Otodontidae and Lamnidae.

I reconstructed the only node that was figured (USNM 474998) as an O. megalodon pup. The silhouette is based on Oliver Demuth’s artwork in Cooper et al. (2020), which in turn was based on the rigorous model created for that paper. The estimated total length is 1.46 m (4.8 ft) from the end of the rostrum to the end of the upper caudal lobe. The birth size of O. megalodon was recently estimated to be 2 m (6.6 ft) total length (Shimada et al. 2021). This means that this individual was a late stage fetus, which would be the first record of an unborn megalodon to my knowledge. Alternatively, if it was the smaller Parotodus it more likely would have been a newborn.

References

- Agassiz, J.L.R. (1835). Kritische revision der in der Ittiolitologia Veronese abgebildeten fossilen fische. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde, 1835, 290-316.

- Cooper, J.A., Pimiento, C., Ferrón, H., & Benton, M.J. (2020). Body dimensions of the extinct giant shark Otodus megalodon: a 2D reconstruction. Scientific Reports, 10: 14596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71387-y

- Davis, J.W. (1887). The fossil fishes of the chalk of Mount Lebanon, in Syria. Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society, Series 2, 3, 457-636.

- Purdy, R.W., Schneider, V.P., Applegate, S.P., McLellan, J.H., Meyer, R.L., & Slaughter, B.H. (2001). The Neogene sharks, rays, and bony fishes from Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, 90, 71-202.

- Mollen, F.H., & Jagt, J.W.M. (2012). The taxonomic value of rostral nodes of extinct sharks, with comments on previous records of the genus Lamna (Lamniformes, Lamnidae) from the Pliocene of Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina (USA). Acta Geologica Polonica, 62(1), 117-127.

- Shimada, K., Bonnan, M.F., Becker, M.A., & Griffiths, M.L. (2021). Ontogenetic growth pattern of the extinct megatooth shark Otodus megalodon – implications for its reproductive biology, development, and life expectancy. Historical Biology (in press). https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2020.1861608

- Volta, G.S. (1796). Ittiolitologia Veronese del Museo Bozziano ora annesso a quello del Conte Giovambattista Gazola e di altri gabinetti di fossili Veronesi. Stamperia Giuliari.

- Woodward, A.S. (1889). Catalogue of the Fossil Fishes in the British Museum (Natural History). Part I. Containing the Elasmobranchii. Trustees of the British Museum.

Addendum (6/4/2022)

I have published an updated version of this list in my open-access paper “List of skeletal material from megatooth sharks” in the journal Paleoichthys. It contains an additional 9 specimens not included here, as well as new information and references for some of the 14 included here.

Addendum (11/22/2022)

I have published “Additions to ‘List of skeletal material from megatooth sharks’, with a response to Shimada (2022)”. This paper adds two specimens to the list, including a mostly complete body fossil of Cretalamna with soft tissues. It also addresses criticisms of my first paper.

Institutional abbreviations

IRSNB – Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Brussels, Belgium

LACM – Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, USA

MGUH – Geological Museum, University of Copenhagen (formerly Museum Geologicum Universitatis Hafniensis), Copenhagen, Denmark

NMV – Melbourne Museum (formerly National Museum of Victoria), Melbourne, Australia

OU – University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

UF – Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

USNM = National Museum of Natural History (formerly United States National Museum), Washington, DC, USA

| Taxon | Specimen(s) | Material | Provenance | Age and references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cretalamna hattini | LACM 128126 | ~120 teeth, both palatoquadrates, both Meckel’s cartilages, 35 vertebrae | Niobrara Fm., Kansas, USA | Late Cretaceous1,2 |

| Otodus obliquus | UF 162732 | unspecified numbers of teeth and vertebrae | Khouribga phosphates, Morocco | early Eocene3,4 |

| Otodus auriculatus | IRSNB P809 | 34 teeth, 50+ vertebrae | Brussels Fm., Belgium | middle Eocene4,5,6 |

| Otodus angustidens | IRSNB P929 | 97 teeth, 77 vertebrae | Boom Clay Fm., Belgium | early Oligocene4,6,7 |

| Otodus angustidens | OU 22261 | ~165 teeth, 32 vertebrae | Otekaike Limestone Fm., New Zealand | late Oligocene8 |

| Otodus angustidens | NVM P253864 | 33 teeth, 1 vertebra | Jan Juc Fm., Australia | late Oligocene9,10 |

| Otodus megalodon | IRSNB P9893 (formerly IRSNB 3121) | ~150 vertebrae | unknown fm., Belgium | middle – late Miocene4,11,12, 13 |

| Otodus megalodon | MGUH coll. | ~20 vertebrae | Gram Fm., Denmark | late Miocene14 |

| ?Otodus megalodon or ?Parotodus benedeni | USNM 474994 – USNM 474999 | 6 isolated rostral nodes | Yorktown Fm., North Carolina, USA | early Pliocene15,16 |

References

- Shimada, K. (2007). Skeletal and dental anatomy of lamniform shark, Cretalamna appendiculata, from Upper Cretaceous Niobrara Chalk of Kansas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27(3), 584-602.

- Siversson, M., Lindgren, J., Newbrey, M.G., Cederström, P., & Cook, T.D. (2015). Cenomanian-Campanian mid-palaeolatitude sharks of Cretalamna appendiculata type. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 60(2), 339-384.

- MacFadden, B.J., Labs-Hochstein, J., Quitmyer, I., & Jones, D.S. (2004). Incremental growth and diagenesis of skeletal parts of the lamnoid shark Otodus obliquus from the early Eocene (Ypresian) of Morocco. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 206, 179-192.

- Ehret, D.J. (2010). Paleobiology and taxonomy of extinct lamnid and otodontid sharks (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii, Lamniformes) (Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida). University of Florida Digital Collections. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UFE0042397/00001/pdf

- Storms, M.R. (1901). Sur un Carcharodon du terrain Bruxellien. Mémoires de la Société Belge de Géologie, de Paléontologie et d’Hydrologie, 15, 259-267.

- Nolf, D. (1988). Dents de Requins et de Raies due Tertiare de la Belgique. Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique.

- Leriche, M. (1910). Les poissons Tertiaires de la Belgique. III. Les poissons Oligocènes. Mémoires du Musée Royal d’Histoire Naturelle de Belgique, 5, 229-363.

- Gottfried, M.D, & Fordyce, R.E. (2001). An associated specimen of Carcharodon angustidens (Chondrichthyes, Lamnidae) from the Late Oligocene of New Zealand, with comments on Carcharodon interrelationships. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 21(4), 730-739.

- Ziegler, T. (2018). Giant shark: a matter of taste. In W. White (Ed.), Dinosaur Dreaming 2018 Field Report (pp. 20-21). Dinosaur Dreaming.

- Ziegler, T., Hocking, D., & Fitzgerald, E.M. (2019). An associated specimen of the lamniform shark Carcharocles angustidens from Victoria, Australia, and evidence of post-mortem faunal succession. In A. Farke, A. MacKenzie, & J. Miller-Camp (Eds.), Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, October 2019, Abstracts of Papers, 79th Annual Meeting (pp. 224-225). Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- Leriche, M. (1926). Les poissons Tertiaires de la Belgique. IV. Les poissons Neogénès. Mémoires du Musée Royal d’Histoire Naturelle de Belgique, 32, 367-472.

- Gottfried, M.D., Compagno, L.J.V., & Bowman, S.C. (1996). Size and skeletal anatomy of the giant “megatooth” shark Carcharodon megalodon. In A.P. Klimley & D.G. Ainley (Eds.), Great White Sharks: The Biology of Carcharodon carcharias (pp. 55-66). Academic Press.

- Shimada, K., Bonnan, M.F., Becker, M.A., & Griffiths, M.L. (2021). Ontogenetic growth pattern of the extinct megatooth shark Otodus megalodon – implications for its reproductive biology, development, and life expectancy. Historical Biology (in press). https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2020.1861608

- Bendix-Almgreen, S.E. (1983). Carcharodon megalodon from the Upper Miocene of Denmark, with comments on elasmobranch tooth enameloid: coronoïn. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, 32, 1-32.

- Purdy, R.W., Schneider, V.P., Applegate, S.P., McLellan, J.H., Meyer, R.L., & Slaughter, B.H. (2001). The Neogene sharks, rays, and bony fishes from Lee Creek Mine, Aurora, North Carolina. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, 90, 71-202.

- Mollen, F.H., & Jagt, J.W.M. (2012). The taxonomic value of rostral nodes of extinct sharks, with comments on previous records of the genus Lamna (Lamniformes, Lamnidae) from the Pliocene of Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina (USA). Acta Geologica Polonica, 62(1), 117-127.

I really appreciate the effort you put into all of your posts, but specially this one, since I’ve been interested in empirical info about megatooths for a long while :] Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person